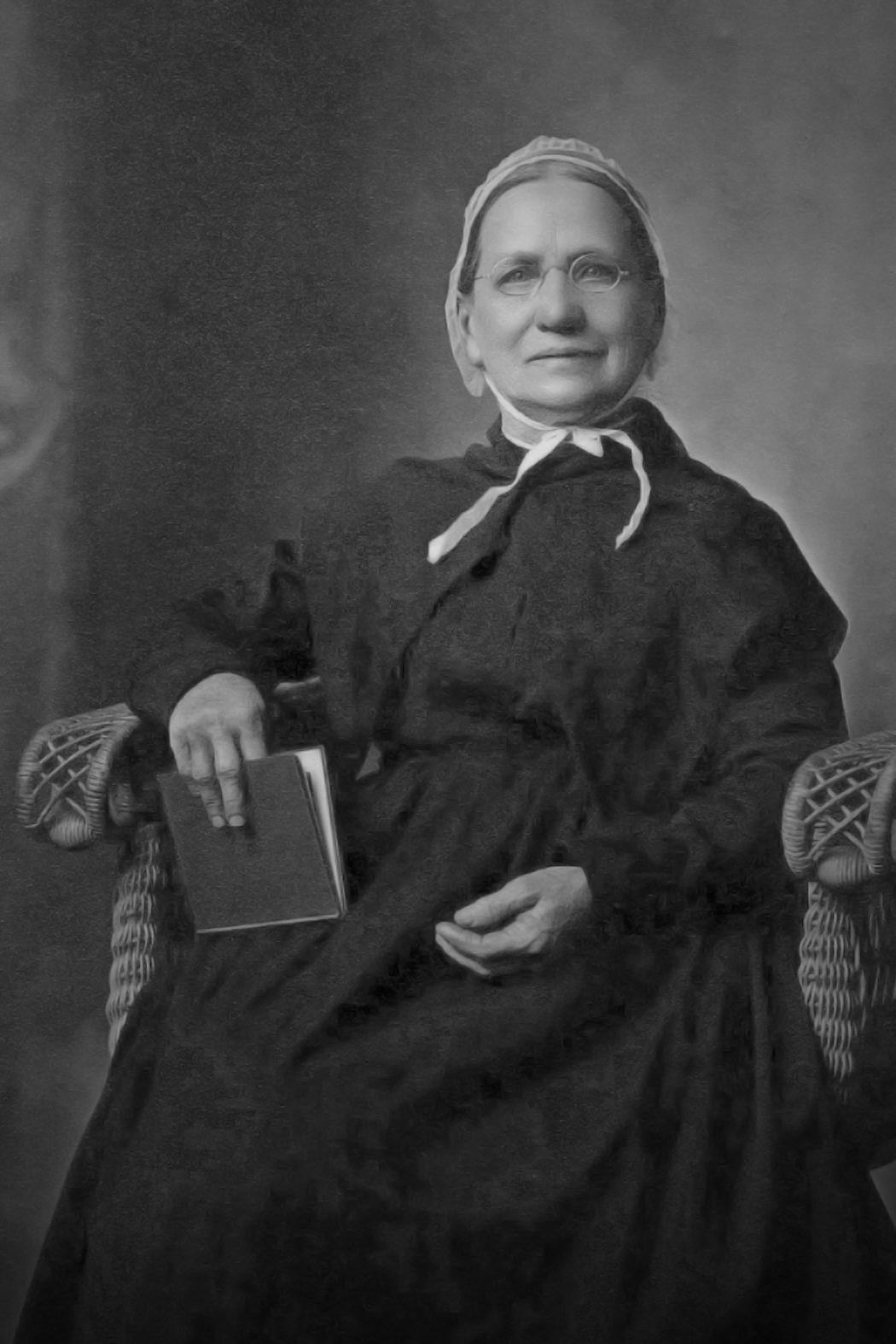

Julia Gilbert was baptized at the age of 14. That’s when the trouble started. Of course, this depends on your perspective. Gilbert lived during a time in the Church of the Brethren that kept men and women separate during rituals such as footwashing. Additionally, the sisters were denied the privilege of breaking bread and passing the cup of communion among themselves. A [male] church elder would break the bread for them. It is speculated that this was done to symbolize the headship of man over woman. Or perhaps, as Pamela Brubaker notes in a chapter of Church of the Brethren: Yesterday and Today, “a change was made so that the administrator could be sure that women whose heads were not properly covered would not be able to receive communion, thus assuring their obedience to church authority.”

Whatever the reason, Julia found this practice frustrating due to her diligent study of scripture and her concern that that the practice of the church be faithful to biblical teachings. That led her to believe that women should be allowed to break bread for each other during communion following the example of Christ. “In 1883 she wrote a letter to the Gospel Messenger asking if those who taught that women were subordinate under the law and gospel and therefore should not break bread with each other would please instruct the sisters what to do during feetwashing and the salutation of the holy kiss.”

Queries requesting that the privilege of breaking bread and passing the cup be granted to sisters came regularly to Annual Meetings beginning in 1899. The queries were coming from Grundy County (Iowa), and they were written by Julia Gilbert. Brubaker explains “About this time claims were again made that the sisters had broken bread for each other in the early days of the church. Drawing on historical material from the library of Abraham Harley Cassel, historian Martin G. Brumbaugh concluded: ‘Enough has been recorded to show that at the beginning, and at least for fifty-four years, in the early church the sisters were treated exactly like the brethren, and each one passed the cup and broke the communion bread.’ … There are presently no documents available from early Brethren history that clearly establish that sisters did break bread. But there is evidence that leaves the question open. In discussing communion in his Rights and Ordinances, Alexander Mack, Sr. made no reference to different modes of breaking bread for sisters and brothers…. Brumbaugh’s claim was incorporated into the next query to come to Annual Meeting [in 1906] asking that sisters be granted the privilege of breaking bread and passing the cup. The author…was Julia Gilbert. Again, a study committee was appointed by Annual Meeting.

This committee reported in 1909 that, after study, they too found that the administrator should break the bread for all participants, men and women alike. The report was deferred for one year. At the 1910 Annual Meeting, several speakers criticized the report and instead proposed that the sisters be given the same right to break bread enjoyed by the brothers. Julia Gilbert rose to speak…on behalf of the sisters from the Grundy County Church, thus becoming the first woman known to have spoken during business sessions at Annual Meetings. She began by giving the reason why the query had been brought, pointing to the covenant she and others had made at baptism ‘to live faithful to Christ Jesus until death.’ In the words read at every communion, she said, Paul commanded: ‘Be ye followers of me as also I am of Christ’ … He followed Christ in breaking the bread, and therefore, I think I have the right to ask these delegates to permit the sisters to break bread one to another.’ The request was finally granted. Oneness in Christ Jesus ruled out man exercising headship over women during the communion.”

Julia Gilbert died in 1934, but her courage and persistence in the “struggle for the sisters to break bread,” brought lasting change to the church and hastened the day in which women would gain “full and unrestricted rights in the ministry” from the 1958 Annual Conference. These changes to polity have not yet resulted in the equal participation of women in leadership but they remind us of the grit required to overcome resistance to a more inclusive church and are most worthy of celebration.

Source: Church of the Brethren: Yesterday and Today, edited by Donald F. Durnbaugh, 1986